Rock and Roll in Italy

American rhythms and dances had set foot in Italy in the 1920s, and an important strand of our song repertoire that exploded in the wake of World War II owes a fundamental debt to swing. In the 1950s, the process of Americanization proceeded even faster, and the new generations seeking change identified it in rock and roll. The dance and its culture took root in Italy in a transversal and unusual way, encouraging the rush to imitate, creating hybrids and desecrating parodies.

NAPLES AND NATO BASES IN THE 1950s

(Marilisa Merolla)

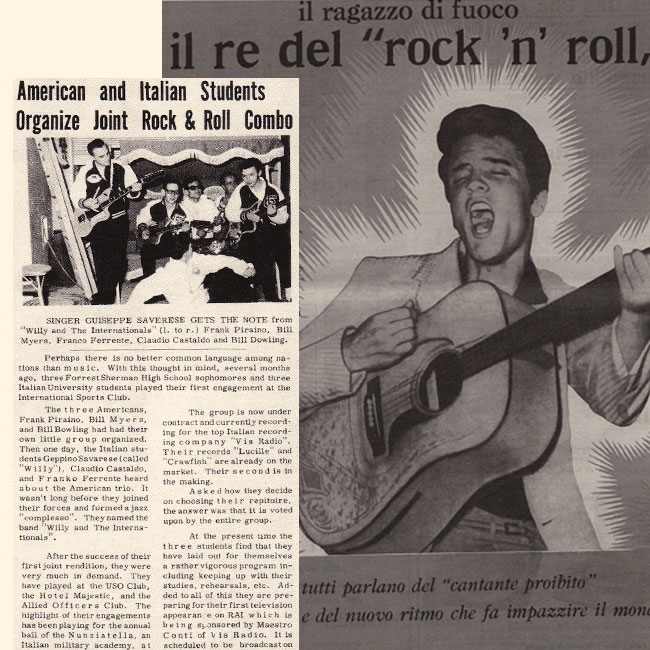

Even more than school visits, recreational gatherings such as parties, dance parties, shows and concerts were the real contexts for cultural integration, when the new trends in clothing, dance, music, and screamed songs were copied directly from the American peers. Even Italian classics such as Volare were revisited in American-style energetic interpretations. Young women experienced a real advance in emancipation, starting with the school group “Shermanettes”, the first female music band which was formed in Naples. Males or females, Neapolitans or Americans, all went crazy for the home-grown rock and roll bands, such as Willy and the Internationals, the group made up of the students from Frank Piraino’s Sherman School, Bill Meyers and Bill Dowling, and three Neapolitan university students, Geppino Savarese (Willy), Claudio Castaldo and Franco Ferrante. They had won a contract with the record company VIS Radio and an appearance on television thanks to a frenzied version of Lucille, the hit by black rock and roller Little Richard.

Marilisa Merolla, Rock’n’Roll Italian Way. Propaganda Americana e modernizzazione nell’Italia che cambia al ritmo del rock (1954-1964), Coniglio Editore, Rm, 2011, p.32.

TU VUO’ FA’ L’AMERICANO

(Alessandro Portelli)

The mass culture of provincial Italy stood up to the challenge of the American products seeking to absorb them with the least possible damage […] But the significant fact is that, while making fun of rock and roll, even Tu vuo’ fa l’americano was one of the Italian songs that best used the style of rock and roll. Therefore, more than an act of opposition to the new music, it is an attempt to assimilate it by making it familiar, reducing it to the Neapolitan style of a kind of ironic Posillipo-rock that strips the foreign and aggressive new style of its alienation and estrangement […]. This American music tumbled onto the national scene without warning and without discrimination. We lacked the tools to distinguish the different strands and the different traditions of Rock and Roll […]. For example, the first time I heard Tutti Frutti was in Pat Boone’s version: naturally I convinced myself that Pat Boone was a genius (there was worse: I heard The Great Pretender sung by Flo Sandon’s earlier than by the Platters).

Alessandro Portelli, Elvis Presley è una tigre di carta (ma sempre una tigre), in AA.VV. La musica in Italia, Savelli Rm, 1978, pp.12 and 60.

RICKY GIANCO: ROCK AND ROLL ITALIAN STYLE

(Luigi Manconi)

Gianco is, above all, a rock and roll guitarist and one who sings “Ciuli Fruli” (Tutti Frutti) properly. [… ] It’s easy to say: but Little Richard is something else. So? Here, in Italy, in our province, we needed to make that rhythm, that Little Richard and the wacky world it evoked our own: Ricky Gianco and others like him offered us the version that best fit our needs. Especially since that song with that Italian macaronic title gave the sense of something infinitely workable and adaptable, as malleable as chewing gum. Also, are we sure today that Little Richard’s live version of “Ciuli Fruli” is superior to Ricky Gianco’s? Actually, Gianco’s classic voice and intonation are typical of traditional melody, but influenced by new sounds.

Luigi Manconi, La musica è leggera. Racconto su mezzo secolo di canzoni, Il Saggiatore, Mi, 2012, p. 95.

BRUNO DOSSENA AND OUR OWN “REBELS WITHOUT A CAUSE”

(Dario Salvatori)

Bruno Dossena, Italy’s first and most popular rock and roll dancer, crashed his car on April 17, 1958 […] on the Bergamo-Milan highway, hit by a truck that was moving at high speed in a dark, rain-drenched night. He died instantly […]. In the night clubs, where he had danced since 1951, he was already very popular, with 38 cups and plaques won, including the Italian boogie-woogie title and the world championship (won in Lyon in 1955) for Be-bop, as this dance was surprisingly called then, in a quite erroneous association with modern jazz (…). At Santa Tecla, a historic Milan night club and rock and roll temple, we went to listen to Adriano Celentano, Giorgio Gaber, the Champions, Tony Dallara, Clem Sacco, Guidone, and Ghigo, but the really special evenings were those in which Bruno Dossena was unleashed on stage, demonstrating to all those young budding talents what could be done with that rhythm that came from the States. His way of dancing was pure instinct, musicality, expression of free-flowing movement […]. Bruno Dossena was the first rock and roll hero. For Milanese fans he was certainly a legend, but also the first tragic victim, the emblem of a rough and ready, insouciant youth, pale as a secret melancholy but extraordinarily charged with energy, able to thrill people and make them happy.

Dario Salvatori, Rock Around the Clock. La rivoluzione della musica, Donzelli, Rm, 2006, pp. 151-153