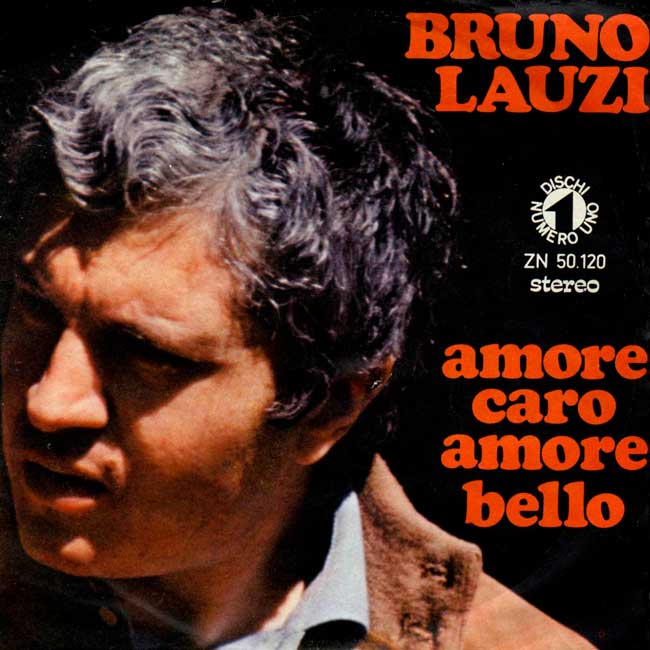

Amore caro, amore bello

Amore caro, amore bello

Amore caro, amore bello

(Dear Love, Beautiful Love) (Lucio Battisti-Mogol) – Bruno Lauzi – 1971

My philosophy professor at the glorious D’Oria high school for classical studies in Genoa always said to be wary of those who are unclear and don’t make themselves understood because “He who doesn’t make himself understood either does not understand himself or is interested in not being understood”, he said. He seemed to have guessed what would’ve happened with our Battsti & Mogol in 1971, when I was given the new song actually written and arranged just for me, so much for me that it is the only song of Battisti’s that he never sang, to the point that he said, “I could never sing it better than you”. Flattering, undoubtedly, but what was I singing? I found myself in the ridiculous situation of having to ask the author for a translation. For example, verses like:

Sincera,

come l’acqua di un fiume di sera,

trasparente eppur sembri nera

(Sincere,

like the water of a river in the evening,

transparent yet seems black)

and again

ho visto

cattedrali di luce nel cuore

troppo sole può farmi morire

(I’ve seen

cathedrals of the light in the heart

too much sun can make me die)

What did they mean?

Very simple: she betrayed him and the sincerity of the confession leads to the inevitable consequence that her black sinful essence is discovered, and that the sudden and violent revelation of the truth is unbearable. Well, let me say that I find the hermeticism of Ungaretti and Montale nobler.

I’m sorry to bite the hand that feeds me, but I’ve hated Amore caro amore bello since Day One; however, I’m a professional and I’m not “abelinato”, a fool, either. I hate its melodramatic quality, that rhetorical cry in the bridge:

Le mani, non le ha, oppure si?

E poi cos’ha?

Ah, io muoio!

(Hands, she doesn’t have any, or does she?

And what else does she have?

Ah, I’m dying!)

The pathetic lament of a cuckolded whiner. It’s not exactly my style, the whining, I mean.

New Year’s Eve in’71 in Rio de Janeiro, the home of Juca Chaves, who’s explaining to his carioca friends who I am and that in that moment I’m at the top of the Italian Hit Parade. Everyone is giving me compliments and boisterously asking me to sing the song. I grab a guitar and sing and play it. At the end there’s a moment of silence and then Juca exclaims. Astonished, stammering with surprise, he says “But, this is Opera”. Judging from his grimace I immediately understand that this is not a positive criticism. How well I understand them! For those who’ve grown up on bread and samba from infancy, the 19th-century language of the song makes them laugh, doesn’t move them, exactly the opposite of what happened in Italy.

One day, Lucio gave me one of the nicest complements I’ve ever received. He said, “You’re the only one among those who sing my songs that makes it yours to such an extent that a lot of people ask me if you’ve written any other ones for me”. Something that has happened regularly numerous times, consecrating me as a performer and freeing me from the complex of the singer-songwriter who is a “traitor to the cause”.

Estratto da: Lauzi, Bruno, Tanto domani mi sveglio. Autobiografia in controcanto, Sestri Levante, Gammarò Editori, 2006, pp. 89-9