C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones

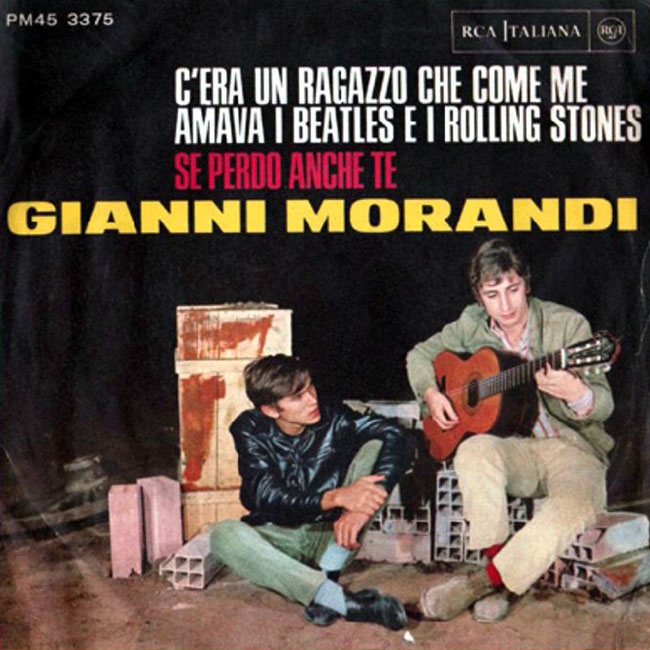

(Mauro Lusini-Franco Migliacci) – Gianni Morandi, 1966

The composer was Mauro Lusini, while Franco Migliacci had written the lyrics in ten minutes, between the first and second courses in a typical Rome tavern. Franco had written them for him, the person who would shortly record the song. And Mauro was proud. He understood that he finally had a great opportunity to get noticed on the scene of those years. But I deployed all the stubbornness of somebody born in the mountains to make sure that the song was left to me. The recording company RCA was against it. The director, Ennio Melis, who until then had been one of the engineers behind my success, said it would be my downfall: Morandi could not possibly sing such a revolutionary song. People wanted a romantic, smiling Gianni, the eternal carefree youngster you might meet in your neighbourhood, not an indolent troublemaker. Leave protests to others! I held on as never before until, in December 1966, at the Festival delle Rose at the Hilton in Rome, I was threatened with being obscured by the RAI if I were to sing the words “Vietnam” and “Vietcong”. It was at that point that I shocked everyone. This is how I did it.

Before the performance, Migliacci was at the receiving end of Melis’ angry outburst, who put him on the phone with RAI executives who forced him to change the lyrics of the song at that critical point. They said they already had a solution: put “Corfù” and “Cefalù” instead of “Vietnam” and “Vietcong”. Cefalù? Corfù? Are we joking? Migliacci could not accept such a position, even if the penalty was censorship and even worse: things went as far as to say that our country could not afford to stand against an allied nation through the voice of one of its most popular singers. Migliacci and Morandi even risked the withdrawal of their passports. Franco hastily joined me in the dressing room, just before the live broadcast. He closed the door and quickly explained the situation to me. There’s nothing you can do, real talent comes to the fore in the face of difficulty. Franco told me very calmly: “Let’s do it like this. Instead of Vietnam and Vietcong, you’ll sing: they told me to go ta-tatà and shoot tatata … tara-ta-ta-ta, tara-ta-ta-ta”. I got the message, and showed up on the stage. As I came out, I noticed the presence of threatening shadows hidden in the wings of the theatre. I was surrounded by all the musical and television high command of those years, an array that made me feel excited. Finally my turn came, the lights went out and I saw the red light of the huge camera waiting for my big beautiful face to fill the screen. A sense of power invaded me and finally gave a meaning to the adrenaline that was coursing through me. A beam of white light came on which my eyes did not fear. The applause ended, the orchestra began and I knew I had a scream in my throat that would have gone far. C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones, girava il mondo, veniva dagli Stati Uniti d’America… [there was a guy like me who loved the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, he travelled the world, he came from the United States of America …] I had completed the first verse as they wanted. I had avoided the dangerous bone of contention. I obeyed by censoring the disclosure of that Asian trouble, singing the “ta-tatatà” agreed with Franco. But that variation mutilated the song, and made it too banal. I felt like the Salesians, repressed by the discipline of a college. The first song for which I had fought so much …come on, it couldn’t be! “Non ha più amici, non ha più fans, vede la gente cadere giù…” [he has no more friends, no more fans, he sees people fall down…] At that point, literally transported by the strength of the song, I improvised a cunning move to turn away from the cameras. I caught a glimpse of Franco’s shirt collar reverberating in the dark, met his eyes and opened mine wide. The signal was sent. I turned round again to face the audience and found the strength to go right ahead: “Nel suo Paese non tornerà, adesso è morto nel Vietnam! Stop coi Rolling Stones, stop coi Beatles stop” [he will not return to his country, now he died in Vietnam! Stop with the Rolling Stones, stop with the Beatles stop!]”. The cry came out magnificent and balanced, rose imperious, weighing on the whole theatre. I had said it, I’d said “Vietnam”! I had said it and had thrown that perfect harmony of music and words up there. What an incredible sense of superiority! In those years, challenging the authority of the ministers, of the notable defenders of the institutions like that! Naturally, all hell broke loose. The right sided against us and the left in our favour. Despite the risk of having challenged the system, Migliacci was later appointed as the figure that would ensure Mogol and Battisti’s landing in America. Unbelievable.

Quoted from: Morandi, Gianni-Ferrari, Michele, Diario di un ragazzo italiano, Milano, Rizzoli, 2006, pp. 23-25