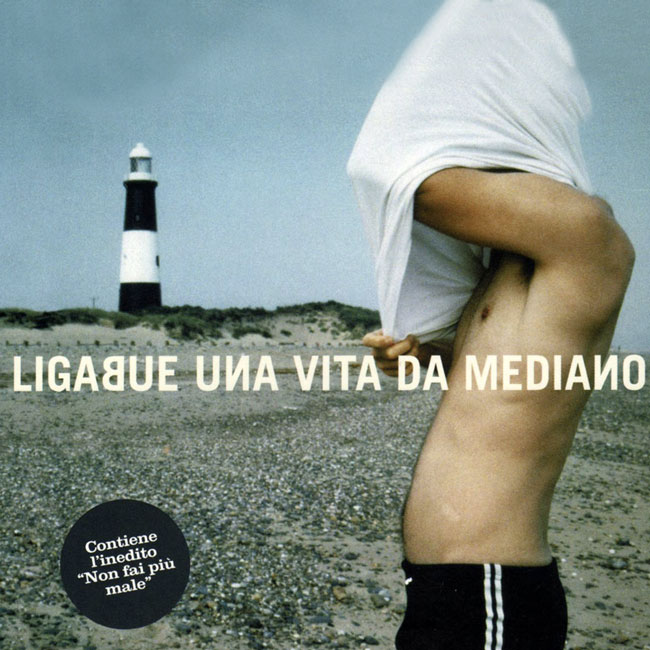

Una vita da mediano

‘Listen, there’s this piece that you made me hear the other day that made an impression on me, Una vita da mediano. It would be a great title for the book. But: how much does it represent you, how much is it really yours?’

It’s very much mine, really. Because apart from the soccer metaphor, it touches on an important point for me, which is that of the effort of living, in the sense that life is a pleasure but also something that one must earn to some extent. I think that people with awareness hardly ever think they’re blessed with genius or talent and that, if they want to produce something, they have to work at it, make an effort. That’s how I am. I wasn’t born with number 10 on my back, I wasn’t born a Platini, a star player: I always had to play in those areas of the pitch like the midfield, and it went well for me anyway, because I originally started out as a goal-scoring defender. This doesn’t mean playing a minor role, on the contrary, it means having a very specific position and task; a role of quality, responsibility, and in the shadows.

The song came about thinking of myself on the soccer field, because, apart from the beginnings I mentioned, I’ve always occupied that position, just above the defense, trying to stop the offense before the final barrier.

‘You’re a ball stealer…’

I am a ball stealer, but I’m also someone who tries for close formations, recalling the team to its position and responsibilities. I’m the way I am in life. And believe me, no one is ever accidentally a goalkeeper, or accidentally a full-back, or accidentally a centre forward.

‘Has there been any great midfielder that made you fall in love with soccer?’

No, no midfielder idols. I don’t even know if that would be possible. I believe that one gets to play midfield more by destiny than by choice, just as in some orchestras, some end up playing certain instruments that are not in the front row. This doesn’t prevent people from being passionate about a midfielder. I don’t know. I suppose we could say that Simeone is a midfielder: today it’s practically impossible to still call the new roles by the old names, with those midfield lines moving back and forth. However, let’s suppose that Simeone is a midfielder. Well, people love him, for his determination, for what he puts into it, for the fact that every now and then he takes one for the team. It seems to me as well that those types of players have a special gift, that is, that extra soul, that “feeling of belonging” that ultimately wins over the fans. But then when the fan goes to buy the jersey, he doesn’t buy Simeone’s 14, he buys Ronaldo’s 9.

‘But in the text you quote Lele, you quote Oriali. Is he in some way your role model?’

I quote Oriali because, when talking about these things, I think back to a touching image from several years ago. I’ve never specifically been a fan of his, I mean when he played for Inter. But there’s this image of the World Championship final against Germany that excites me. Oriali was literally beaten to a pulp. He sacrificed himself through physical pain to hang on to the ball, to buy time. He played a game of nerves, of tension. And I think if I’d had to give him a vote on a strictly technical basis, it wouldn’t have been very high. However, if you take into account the generosity, the presence, the time spent getting kicked by Stielike, well, he played a crucial role. Here, the Oriali of the song is this quality: someone who puts everything he has and even more into it, who pushes his own limits.”

Excerpt from: Bertoncelli, Riccardo, Una vita da mediano. Ligabue si racconta, Florence, Giunti, 1999, pp. 11-12